Art as a bridge serves several purposes. As a bridge to other people, art helps us understand and empathize with individuals and people groups we don’t understand, whether because of long distances of time and space or because of long distances between their ideology and ours. This is huge. What we don’t understand we fear. When we act out of fear, we fail to live by faith and to act out of love. Conversely, understanding brings connection and the ability to empathize. Empathy, or compassion, or love-induced understanding, is a pillar of our faith. How can we show Christ’s love to people we choose not to connect to and empathize with (whether by willful choice or lazy neglect)?

Finally, art serves as a bridge to the Other, to God. We need imagination to envision the Kingdom of God, a world which Jesus said was here but not yet fully here. We need our God-given imaginations to pray, Father, make it on Earth as it is in heaven. Art helps us go there, helps us engage our imaginations. It can take us to otherworldly places like Narnia and Hogwarts and Middle Earth. In a painting, lovers can float happily above the world of cares and woes, as if in heaven. When art depicts light and life and love through colors and lines and shapes (and cinematography and dialogue and chord progressions), art is, whether we realize it or not, whether the artist intended it or not, pointing us to the Source of light and life and love, to Light and Life and Love himself!

Even when art shows us the shadows, when we’re forced to face all that is dark and dead and ugly in the world (and in our hearts), this too points to God and to Christ. Like the negative of a photograph shows us what should be fully there but isn’t, this kind of art shows us our fallen condition, often pointing to the reality that begins to take shape when God is taken out of the picture, when sin has pushed him out of the framework of our lives.

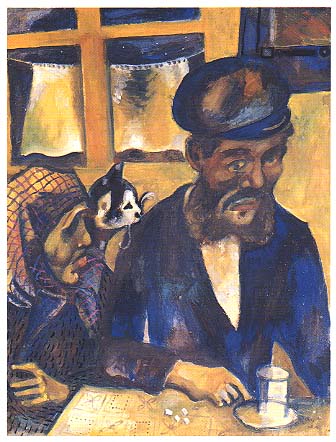

With these concepts in mind—art as mirror and bridge—let’s practice engaging with art with one of my favorite painters. The paintings of Marc Chagall are characterized by his use of rich, vibrant colors; floating, elongated figures; and life-bearing imagery and symbols: such as fruit, flowers, streams, trees, chickens, bulls, lovers... In 1914, Chagall was in his hometown Vitebsk, Russia with his fiancee Bella Rosenfeld, with whom Chagall intended to return to Paris, but was prevented from doing so when the Great War broke out. This war-affected stint in Russia resulted in a major shift in Chagallʼs paintings. Gone are the vibrant colors. Gone are much of the influences of cubism and the life-bearing images and symbols. All these are replaced with browns and greys, downcast figures, and a thematic and stylistic shift toward realism — Paris is exchanged for Russia, peacetime for wartime.

We can see this shift notably by comparing Chagallʼs Paris through the Window of 1913 to his work titled, Father, from 1914. Note in Paris through the Window the rainbow-like reds, greens, yellows, blues, and oranges. Note the fanciful and strange (but wondrous-strange) figures and goings-on: the upside-down train, the man floating down from the Eiffel Tower, the couple floating horizontally in head-to-head conversation, the colorful cat with the human face, the cheerful bouquet of flowers, and finally, the two-faced figure looking out the window into the city (and looking back, presumably to Vitebsk).

|

| Paris through the Window, oil on canvas |

All this vibrancy and fancy and glorification of the realm of imagination is abandoned as the weight of war forces Chagall, even Chagall who was so resilient against his contemporaries’ compulsions toward total abstraction, to morph from a bridge between reality and imagination—a soul connecting body and spirit—into a mirror of the reality of Chagallʼs war-burdened world, bringing the everyday and the ordinary into perspective.

|

| Father, tempura on paper |

When we look at Chagallʼs Father with 21st century eyes, the piece serves as a bridge: the gap is bridged between 21st-century America and early 20th-century Russia as we understand WWI Russia a bit better, as we understand Chagall a bit better (the painting is of his father and grandmother), and most significantly, as we empathize with the double burden of war and poverty. For many it no doubt also serves as mirror: we can see our own present economic struggles in the slumped shoulders, downcast eyes, and barren table. Contextual specifics do not cloud universal translation—that’s good art. Father is the two-faced figure from Paris through the Window looking back to itʼs own wartime context and looking out into our present one.

1 comment:

"Even when art shows us the shadows, when we’re forced to face all that is dark and dead and ugly in the world (and in our hearts), this too points to God and to Christ." Yes, yes, yes!!

Post a Comment